Theory

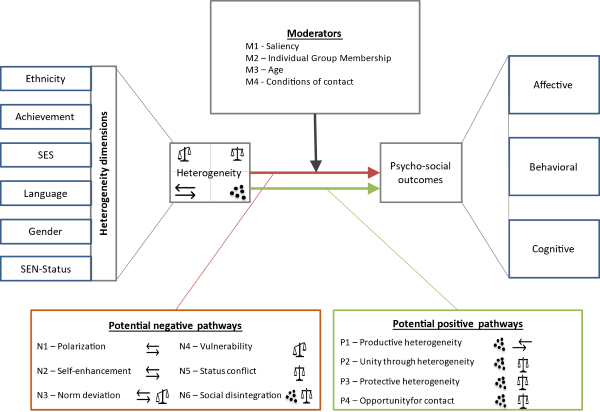

Many theories have been developed that either set out to describe the impact of group heterogeneity on social and psychological outcomes or have implications for this link. Based on a review of relevant theories from developmental psychology, social psychology, sociology and politics, we have developed an integrated theoretical model of the effects of classroom heterogeneity on psycho-social outcomes.

The model describes how classroom heterogeneity on different dimensions is associated with student socio-emotional outcomes.It enumerates ten pathways by which classroom heterogeneity can impact students' psycho-social outcomes.

Heterogeneity

The model doesn't specifically focus on any dimension of heterogeneity. Most pathways can in principle apply to different dimensions of heterogeneity.

The different symbols within the box "Heterogeneity" are signifying that heterogeneity as a term can have different conceptual meanings and implications for measurement, which are, for example, described by Harrison and Klein (2007). In our review of theories, we identified three relevant dimensions of heterogeneity: Firstly, multiplicity, which alludes to the sheer number of different categories present in a classroom. Secondly, the distance between groups or persons: groups can be very similar and close to each other, but they can also spread across a large range. Thirdly, the theme of balance vs. imbalance between groups is a central one, especially to intergroup theories.

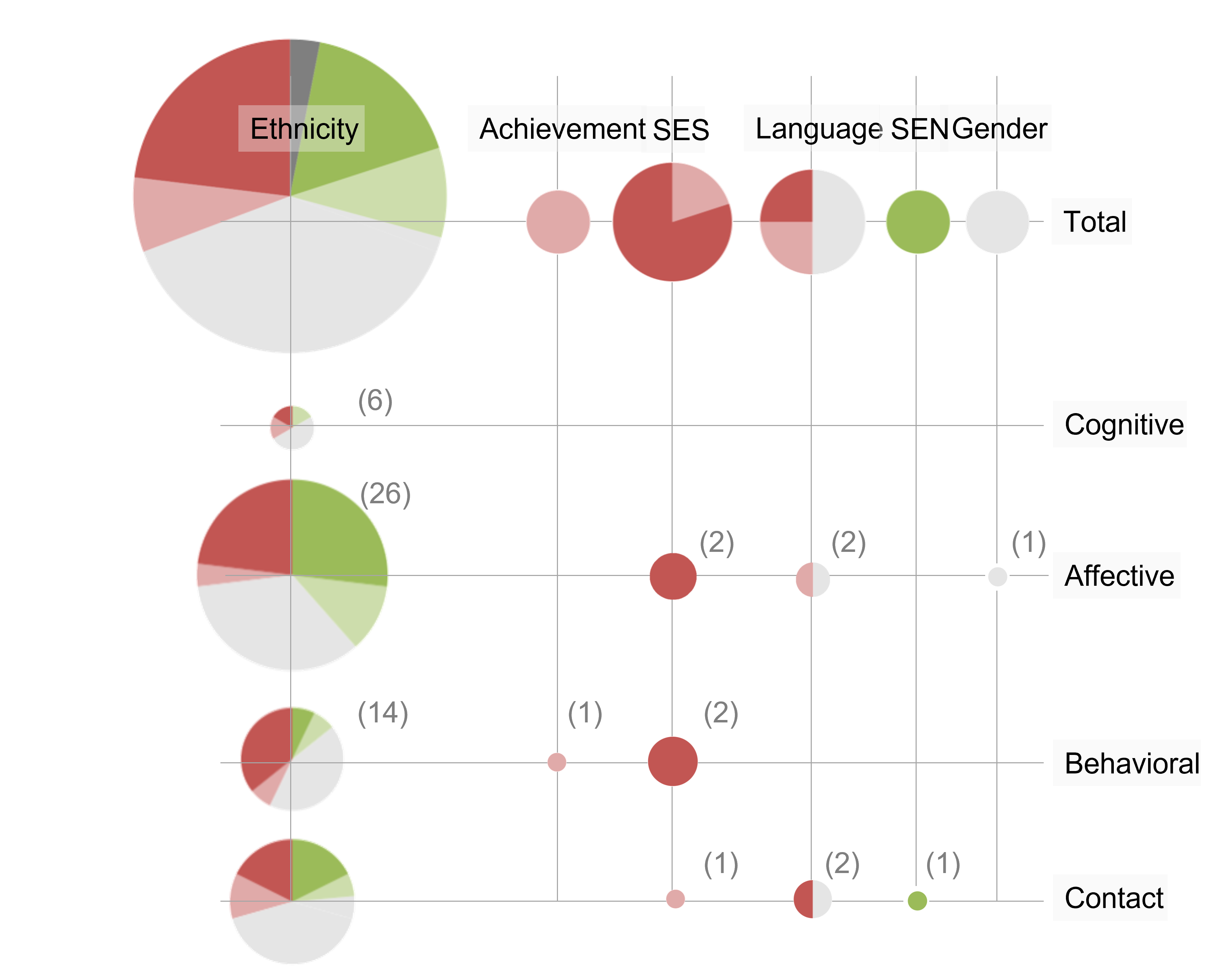

Psycho-social outcomes

The focus in our review of theories was on theories that predict psycho-social outcomes. The targeted outcomes include affective, cognitive and behavioral outcomes, including peer relations. Examples for affective outcomes are school belonging, classroom climate, or subjective social integration. Cognitive outcomes include different interpersonal skills, but also stereotypes. Behavioral outcomes can be aggression, bullying and victimization, but also pro-social behavior and peer support. Also, relationships in the classroom, like number of friends and inter-group friendships, but also homophily, i.e., ingroup-orientation, are included in the review.

Pathways

The pathways by which classroom heterogeneity is hypothesised to cause the outcomes are labeled according to the direction of their influence (P-positive and N-negative). Each pathway is connected to one or more theories from the research fields mentioned above. The symbols next to the pathway signify the conceptualization of heterogeneity which is implicated by the respective theories. In the following, each pathway is shortly described.

N1 - Polarization. Socio-constructivist theorists, like Vygotski and Piaget, emphasize that learning takes place in social interaction with others. Here, differences can have a positive impact in that they stimulate children to exchange their views and ideas and develop more advanced concepts (see below P1). However, if students' prior knowledge and experiences are too different, they might not be able to relate to each other anymore, thus leading to less mutual understanding and ultimately, a polarization in outcomes. For these theories, outcomes are typically in the cognitive realm.

N2 - Self-enhancement. This pathway is described in Tajfel and Turner's Social Identity Theory. This theory posits that humans try to achieve a positive identity by forming groups along a salient social category and then valuing their in-group and de-valuing the outgroup(s). Which identity is salient in a certain situation can be moderated by contextual clues (M1), like teachers emphasizing a dimension of comparison in the classroom, but also by the composition of the class. Thus, low to medium levels of heterogeneity are often seen as causes for saliency of this dimension.

N3 - Norm deviation. This pathway is described by models suggesting negative outcomes for individuals who deviate from a group norm, like the Social Misfit or Person-Group Similarity Model (Wright, 1986) and also Social Comparison Theory (Festinger, 1954, Schachter, 1952). Here, persons deviating from a group norm will have lower status in this group and might even face rejection.

N4 - Vulnerability. Students who belong to a numerical minority in the classroom might be more vulnerable, because they might have less social support than students belonging to a greater group. This is described in Olweus' (1992) Imbalance of Power Thesis. These more vulnerable students are more prone to be victimized by members of the majority group.

N5 - Status conflicts. Contrary to Olweus, Blalock (1967) in his Group Threat Theory predicts that conflict and violence between groups is highest when groups are equally represented and motivated to fight for supremacy.

N6 - Social disintegration. Mostly originating from the study of politics (Constrict Theory, Putnam, 2007) and criminology (Social Disorganization Theory, Shaw & McKay, 1942), this view supposes that in contexts of high diversity (in the sense of ethnic heterogeneity and social inequalities), a missing common identity leads to the dissolution of social control and a break-down of social norms. This in turn creates higher levels of crime and violence and less trust in society.

P1 - Productive heterogeneity. This pathway is based on the aforementioned socio-constructivist theories. Differences are productive in that they throw children in a state of cognitive disequilibrium which they are motivated to resolve by actively engaging in problem-solving, perspective-taking, and dialogue with their peers. This process encourages deeper understanding, critical thinking, and the development of more advanced cognitive frameworks, ultimately fostering intellectual growth and social learning (e.g., of social skills).

P2 - Unity through heterogeneity. This argument proposes that a maximum of heterogeneity will (in the long run) lead to more solidarity and the development of alternative identities that could serve to unite people instead of separating them (Putnam, 2007).

P3 - Protective heterogeneity. Mirroring P4, the idea here is that in a situation in which no clear majorities exist, students are more likely protected from being victimized.

P4 - Opportunity for contact. Finally, in his Structural Theory, Blau (1974) observes that a higher level of heterogeneity increases the opportunity for contact between members of different groups. More contact, provided that it occurs under the right conditions (M4), should lead to more understanding and a reduction of stereotypes.

Neuendorf, C., Hascher, S., Hou, C., Lorenz, G., & Rjosk, C. (2024). Systematic Review: The Effects of Classroom Heterogeneity on Students‘ Socio-Emotional Experiences. Poster presented at the Conference of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychologie in Vienna, Austria

I'm hosted with GitHub Pages.